On Bears and the Berkshires

I lived in Oregon and New Mexico for several years—and backpacked extensively in remote forested wildernesses across the West. So I never imagined that the first time I would ever meet a bear would be back here in my hometown in the Berkshires. Of course, I imagined charismatic megafauna in places like Yellowstone or Yosemite. They wandered in craggy peaks and alpine forest of the Sierras and Rockies. I’ve had plenty of dreams about bears, but I never saw them here growing up. Naturally, now that I’m back East, I’ve had more black bear encounters since September in quaint little Williamstown than I had in my entire time out West.

The black bear population in Massachusetts has been growing steadily since the 1970s to over 4,500 bears currently. Their range now encroaches even on the suburbs of Boston. While I didn’t know it as a kid, I grew up in bear country.

This fall, I ran into a mother and two cubs while hiking on Mt. Greylock with my cousin. It was a moment of sublime witnessing at Stony Ledge. The three of them lumbered onto the trail about 50 yards in front of me and paused, noticing us headed their way. We all froze. The mother and I locked eyes, mutually assessing the risk we signified to each other’s day. And before I could respond with anything resembling prudent risk management, she and the cubs galloped off down the hill.

In both fall and spring, solitary ramblers in black crossed my path while on trail runs in Hopkins Forest and on Stone Hill mere minutes from the town center. This spring, still another mischievous fellow ransacked our birdfeeders and our neighbors’ garbage twice in the night. We’ve since learned to adapt and remove food sources, but it was quite the surprise and delight to catch that cheeky offender on night on video in the beam of my flashlight. Watching from the roof of our porch, I could see he was a regular Pooh. He clambered up the trunk of the apple tree, cautiously waddled out onto the main branch to grab the suet feeder, accidentally dropped it on his way down, and then fumbled around with the wire cage of the suet cake until the fatty treat was unlocked and devoured. The charming magic of the more-than-human world incarnate!

The black bear population in Massachusetts has been growing steadily since the 1970s to over 4,500 bears currently. Their range now encroaches even on the suburbs of Boston. While I didn’t know it as a kid, I grew up in bear country. Learning to live with bears is becoming a regular feature of life here, and it’s a blessing to have such charming neighbors roaming the land.

Collaborative Conservation in New England

One of the reasons such a population has established and thrived here in the Berkshires is that approximately three-quarters of the county is forested, and over a third of that land is under some form of permanent conservation protection. This is in no small part due to the work of organizations like the Berkshire Natural Resources Council (BNRC). So, really, it shouldn’t be a surprise that we have a plethora of wildlife here.

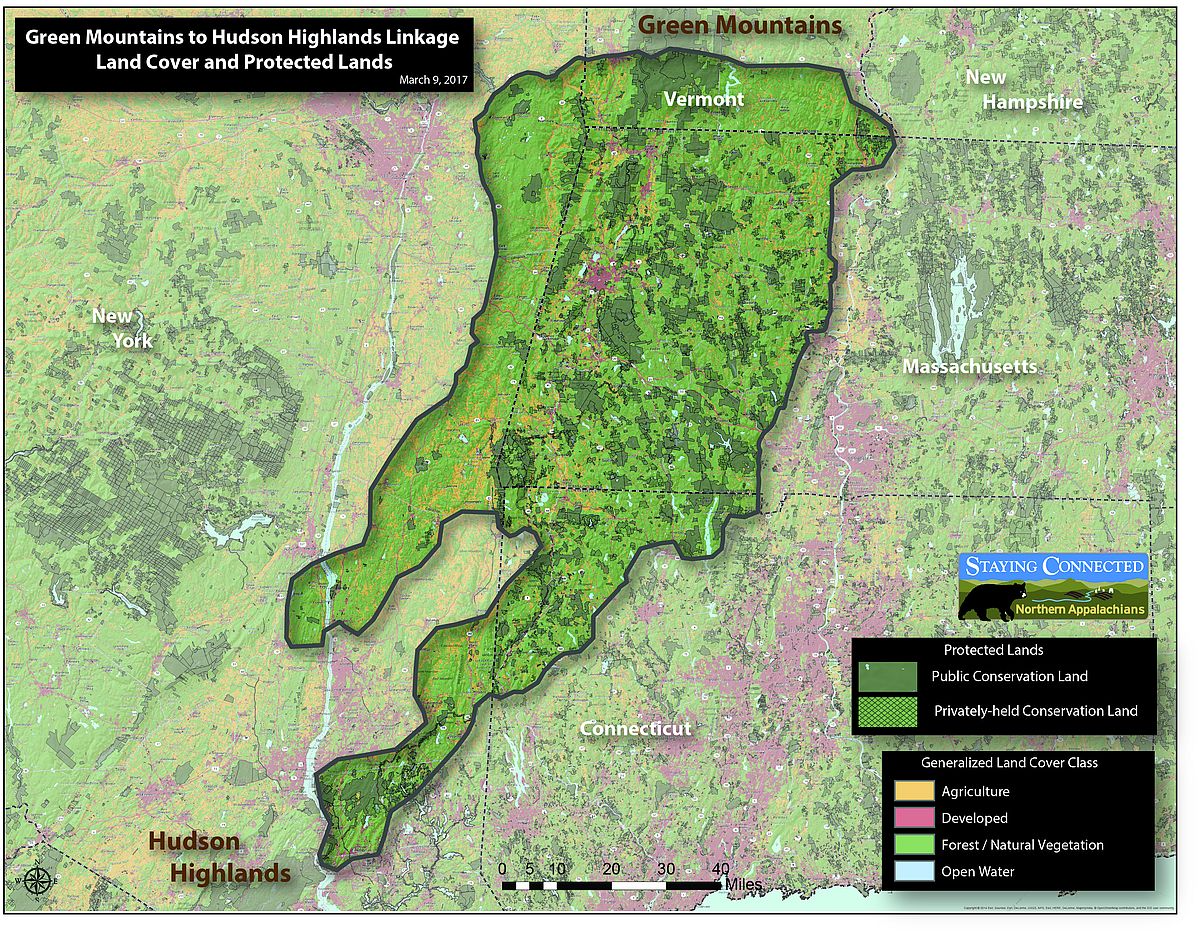

After all, the Berkshires are a critical wildlife corridor in the long chain of the Northeast Appalachians. They connect the Hudson Highlands to the Green Mountains and other ranges farther North. These hills and forests enable the continued movement of wildlife along that north-south axis. Such corridors will become critically important for wide-ranging mammals like black bears, moose, or bobcats in the era of abrupt climate change. Adapting to changing conditions may require substantial migrations—both for humans and our more-than-human kin.

These larger species, which require the largest tracts of contiguous habitat to thrive, are bellwethers for the health of the land and ecosystems in general. If there’s enough of a patchwork of protected lands with varied latitudes and elevations for them to survive at the higher levels of food chains, then species with smaller ranges will hopefully have ecological niches to thrive as well. Our relationships to large, wide-ranging species may well be a profound indicator of our capacity for empathy for the natural world in general.

Ambitions to increase conservation require diverse stakeholders for success. Regional organizers are critical for large-scale planning and organization. And smaller land trusts like BNRC must maintain intimate relationships with landowners, monitor conservation restrictions, and change hearts and minds in local communities.

There are many organizations that are instrumental in creating the mosaic of conserved lands that will provide such necessary refuge for wildlife. A less-than-exhaustive list includes BNRC, Mass Audubon, The Trustees of Reservations, the Berkshire Environmental Action Team (BEAT), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), and many local land trusts and municipalities. Large landscape conservation often requires Regional Conservation Partnerships (or RCPs) between these many organizations. These networks of varied stakeholders in land protection can develop conservation plans across administrative boundaries. RCPs steward a broad ecological commons that goes beyond categories of private or public ownership.

For instance, the Berkshire Taconic RCP—of which BNRC is a part—focuses on its namesake mountain ranges clustered around the borders of several states. Bears aren’t particularly concerned whether they’re in Massachusetts or New York after all. The Berkshires Taconic RCP establishes a framework to manage and conserve land beyond the constraints of borders. Another collaborative regional vision is the Wildlands and Woodlands initiative—a project of the conservation non-profit Highstead and the ecological researchers at Harvard Forest. They envision conserving over 70 percent of New England as forests in the coming decades. Around 25 percent of the region is conserved forestland now—much of the forestland is unprotected.

Ambitions to increase conservation require diverse stakeholders for success. Regional organizers are critical for large-scale planning and organization. And smaller land trusts like BNRC must maintain intimate relationships with landowners, monitor conservation restrictions, and change hearts and minds in local communities. Regionally and in town, collaboration among a broad network of interdependent partners is key to cultivating ecological resilience.

The Berkshire Wildlife Linkage

One relatively local project within these conservation frameworks is the Berkshire Wildlife Linkage—a project stewarded by TNC. The Linkage aims to alleviate habitat fragmentation and expand wildlife corridors – particularly through areas of human construction and development. The Berkshires have some of the highest concentrations of complex and varied habitats in Southern New England, and TNC and the Staying Connected Initiative identified them as a focal area. The Initiative is an international landscape connectivity collaborative working across the Northeast Appalachian bioregion that aims to conserve forested cores here in the most in-tact temperate broadleaf forest in the world. And it aims to facilitate the free movement of wildlife day to day, seasonally due to migration, and in response to the changing climate. Land trusts like BNRC play a big role in connecting tracts of land for wildlife near developed areas. Its High Road initiative is as critical for its wildlife safety and sustainability impacts as it is for recreational delight.

Another major component of habitat connectivity is creating passages for wildlife to safely cross roads. Every week, my heart breaks to find the body of some fox, beaver, squirrel, or deer mangled on the roadside while I’m out bicycling. Three years ago—and please forgive this grisly image—I nearly lost my stomach contents upon glimpsing the severed upper half of the corpse of a bear by the highway. When I let the feeling of these lost lives in, my conscience demands action and intense scrutiny of the tenets of human exceptionalism. These bears I’m witnessing—so clever and robust in their presence and creativity on the land—are worthy of our love and respect. The roadside deaths, and the property damage and risk to human life they represent as well, are not some unavoidable consequence of development.

The Appalachian Trail, itself a potent symbol for the long corridor of Eastern conserved lands, crosses over 40 roads in 90 miles of trail through the Berkshires. These roads can create isolated habitat islands that are disastrous for their more-than-human inhabitants.

In fact, earlier this year, Sweden made headlines for its plans to build “reno-ducts”—or bridges for reindeer—across several northern roads. The bridges will support the reindeer to cross highways while foraging for lichens that have become more difficult to access due to climate change. Freeze-thaw cycles have begun to trap the lichen under layers of ice, and those layers prevent the reindeer from smelling and accessing the lichen. As the reindeer range northward searching for areas where lichens are more accessible, they must cross roads. Providing safe passage for them supports their capacity to adapt and reduces human property damage and injuries due to motorist accidents.

With major roads like state Route 2 and the Mass Pike bisecting the Berkshires, opportunities abound here as well to ensure wildlife can pass safely under or over our routes of commerce and transit. The Appalachian Trail, itself a potent symbol for the long corridor of Eastern conserved lands, crosses over 40 roads in 90 miles of trail through the Berkshires. These roads can create isolated habitat islands that are disastrous for their more-than-human inhabitants. And they can prevent latitudinal and elevational changes species must make to adapt to a changing climate.

In collaboration with TNC as part of the Wildlife Linkage, BEAT actively advocates for improving roads for both motorist safety and habitat connectivity. For almost a decade now, they’ve used tracking, mapping, and analysis to pinpoint where wildlife cross roads, and they make recommendations to the Mass Department of Transportation on how to alleviate the risks of these crossings. Maximizing motorist safety and minimizing the ecological footprints of roadways turn out to be in distinct alignment. Often, the fix is as simple as requiring small shoreline passages in culverts where roads must already be built over rivers and streams. With much infrastructure due for work already in the coming years, rebuilding plans can accommodate for wildlife.

Toward Intersectional and Interspecies Solidarity

As I reflect on these ways the Berkshires spotlight questions of human development and large landscape conservation, I’m in awe of the challenges and possibilities of building sustainable interspecies relationships in the region. I feel blessed to be able to witness wildlife so regularly, wander woodland paths with abandon, and live in a place where the hills sing purple in the evening. And yet I am anxious about the balance of conserving the magic of this place while still welcoming and defending all those—human and more-than-human—who must make homes here in the coming years.

Reducing the ecological footprint of necessary human development justly and equitably is a critical cornerstone of preserving that magic. So is conserving a broad, durable, and resilient land base for people and our wild companions. The black bears that dance in my dreams and trammel my front yard deserve refuge. And in this era of ecological reconciliation, ethical action demands profound interrogation of the meanings of diversity, equity, inclusion and justice in the human and more-than-human worlds. And I’m grateful to be a part of the fabric of BNRC’s efforts to steward a contemporary ecological commons for the wellness of all beings.

--

A Williamstown native, Christopher Densmore originally fell in love with wild lands as a kid exploring Hemlock Brook—a Hoosac and Hudson tributary with headwaters near BNRC’s Berlin Road Reserve. He earned his BA from Carleton College, worked as a sommelier and outdoor guide in Oregon and New Mexico for several years, and is a student in Eastern Oregon University’s MFA in Environmental Writing. When he isn’t writing or identifying forest flora, he meditates, gardens, and reads abundantly. Christopher’s work with BRNC entails supporting volunteers, curating communications, and assisting with education and outreach. He cherishes supporting others to build more intimate relationships with the more-than-human-world.